Grosz Heirs v. Museum of Modern Art

The heirs of the German artist Georg Grosz brought this case in Federal Court in New York to recover three Grosz paintings from the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA).

Grosz emigrated to America in 1933 only weeks before Hitler was named chancellor. The artist left these works among others with his Jewish dealer in Berlin, Alfred Flechtheim, who left Germany for Paris and London within the year. The lawsuit says that following Flechtheim's death in 1937, Grosz's works were sold without the artist's knowledge and each took a different path through the murky art marketplace before, during and after World War II, with all three being acquired by the museum by the early 1950s.

Grosz's heirs and MOMA had discussions, correspondence, and exchanged information for several years; the heirs filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia just a few days shy of three years after MOMA sent a letter saying that the Board of Trustees had voted not to relinquish the art. The museum responded with a Motion to Dismiss arguing that the statute of limitations had elapsed, and on January 6, 2010 the Court agreed with MOMA that the lawsuit came too late. The heirs appealed the decision on January 20, and filed a Second Amended Complaint, answered by the museum on February 1, 2010.

The court's decision may be a departure from previous New York art-recovery cases that hinged on the statute of limitations defense. The "New York rule" (set out in Menzel v. List, a NY decision from the 1960s) requires that a lawsuit to recover stolen property be filed within three years of the original owner discovering its whereabouts, demanding its return, and being refused. Subsequent cases in New York courts and in Federal Courts in the state have tested and clarified many aspects of this rule.

In the Grosz case the court held that the museum had, in effect, refused the plaintiffs' demand for the works' return for at least 18 months before its final letter. The earlier letters and the museum's retaining the paintings meant "no" (even though the word "refuse" was not used) and would stand as a refusal as a matter of law. In so doing, the Court purported to clarifying existing law.

The Court also touched on the question of the heirs' delay in demanding the property decades after they knew its whereabouts. It said that while the delay was irrelevant to New York's three-year statutory period, it was relevant in the context of the defense of laches. However, since the Court found that the lawsuit was time-barred, it did not reach the laches issue (in which the behavior of each party is weighed in the balance -- an equitable defense).

The Grosz heirs turned to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, to reverse the lower court's dismissal of their lawsuit. A large number of interested organizations and individuals filed an amicus brief in support of the appeal. The Appellate Court upheld the lower court’s decision based on its interpretation of the facts rather than the legal issue pertaining to the availability of the Museum’s technical defense.

This is the most recent case in which a museum has brought a claimant for Holocaust-looted art into Federal Court in order to declare that its possession of a painting can no longer be challenged because of the passage of time precluding an independent determination by the court of the merits of the claim. The U.S. Court of Appeals (1st Circuit), noting that the issue of the validity of the transfer of the painting by the original owner “is not clear-cut,” previously noted that since the Museum of Fine Arts had asserted this technical defense, the question was not whether the claimant’s position was “meritorious or not” but whether it could be asserted more than three years after the claimant was found to have been on notice of her claim. The court held that there was no clear evidence of a federal policy disfavoring statute of limitations in cases such as the Terezín Declaration language as being “too general and too hedged.”

This decision followed a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals (5th Circuit) that no federal common law exists that would displace a law that allows the passage of time to prevent the same claimant against another collector because of the passage of time. In this case, as well, the claimant was brought into court by the current possessor of the painting in order to assert a technical defense.

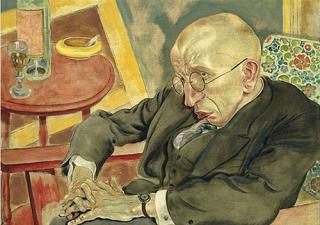

Georg Grosz, The Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse

One of the three paintings the artist's heirs are claiming from the Museum of Modern ArtClaimed

Legal Papers

Legal Papers

- DENIAL OF PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI, October 3, 2011

- United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit: Petition for Rehearing, December 29, 2010

- Grosz v. MoMA 2010 U.S. App. LEXIS 25659, December 16, 2010

- Decision by the United States Court of Appeals (Second Circuit) affirming the Decision of the District Court, December 16, 2010

- Grosz v. Museum of Modern Art, 2010 WL 88003 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 6, 2010), ), reconsideration denied, Mar. 3, 2010. Court Decision Denying Grosz Heirs Motion for Reconsideration, March 3, 2010

- Grosz v. Museum of Modern Art, 2010 WL 88003 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 6, 2010) Court Grants MOMA's Motion to Dismiss, January 6, 2010

Press & Scholarly

Press & Scholarly

- MOMA�s Problematic Provenances - Behind a lawsuit brought against the Museum of Modern Art by the heirs of George Grosz lies a troubling history of acquiring works seized by the Nazis and sold to support the German war effort, William D. Cohan , ARTnews, November 17, 2011

- Family�s Claim Against MoMA Hinges on Dates , Patricia Cohen, The New York Times, August 23, 2011

Affiliated with the World Jewish Congress

Commission for Art Recovery, Inc. | © 2017 All Rights Reserved | Site Index